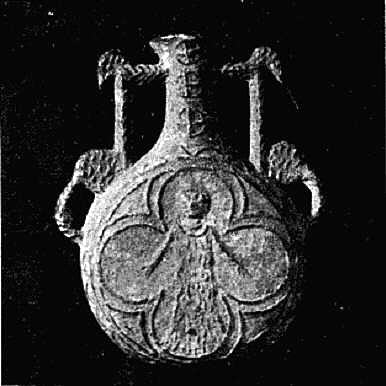

Fig. 2: a more

ambitious forgery, which may have been copied from a genuine

medieval ampulla.

(Courtesy Cuming Museum)

Not surprisingly, the appearance of so many artefacts of a

type hitherto unknown aroused suspicion. Henry Syer Cuming of

Southwark, secretary to the British Archaeological Association,

and Thomas Bateman, the Peak District archaeologist, were

dubious of the examples they saw, and corresponded on exposing

the fraud. Their scepticism was shared by the keepers at the

British Museum5. In March 1858 The Gentleman's

Magazine compared the objects to children's toys and dismissed

them as "almost worthless"6.

By the end of March Henry Syer Cuming had discovered how the

objects were being made. "The game is now almost up, and it is

high time it should be" he wrote7. On 28th April he

lectured on the finds to the British Archaeological Association.

He said that 12,000 has appeared. This was an exaggeration, but

does suggest the speed with which they had circulated and the

interest they had attracted. He pointed out the anachronisms in

their designs, described the crude way in which they had been

manufactured, and concluded by condemning

5. Southwark

Local Studies Library, Ms. 4565; T.B.A.C., 15th Feb. & 2nd April

1858.

6. March 1858 234.

7. T.B.A.C. 29th March 1858.

8. June 1858 649-50.

9. 8th May 1858 595.

10. August 1858 98.

11.T.B.A.C. 4th

Aug. 1858.

12. Proc Soc Ant Lond I ser

4 (1858) 209; Trans London Middlesex Archaeol Soc

1 (1858) 312.

|

them as a "Gross attempt at deception" and regretting that

there were no legal methods of punishing the forgers.

The lecture was not published in the Journal of the

Association, but it was reported in The Gentleman's Magazine8

and Athenaeum9. Sales declined rapidly, and

George Eastwood wrote to The Gentleman's Magazine

assuring the readers of the authenticity of his stock"10.

Meanwhile the eminent archaeologist Charles Roach Smith

inspected the finds. By 1858 he had retired from public life,

but his reputation was still very high. He was not sure what the

objects were, but he felt that they belonged to the 16th

century, partly on the logic that no forger would create

anything so preposterous. If they were forgeries, he wrote, they

would be "The most extraordinary insults that ever were offered

to the judgments of collectors this century"11. The

Reverend Thomas Hugo, vicar of St. Botolph's Bishopsgate, also

took an interest in the finds, believing them to be varieties of

pilgrims' signs12.

But the debate moved away

from academic speculation when George Eastwood sued the

publishers of Athenaeum for libel. He claimed that they

had published an article which accused him of selling forgeries,

for although he was not named, he

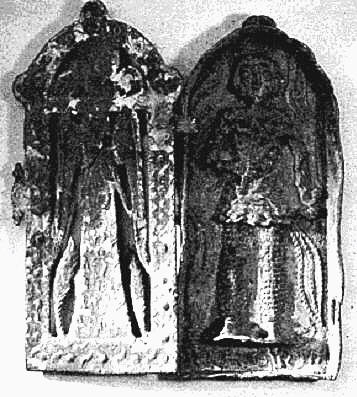

Fig. 3: another ambitious forgery - a small shrine.

Courtesy Curving Museum

|