Turning our back on the Docks, and taking the nearest cut to the Mile-end-road, we will at once dash into Whitechapel; for all behind us belongs to the suburbs, and our present descriptions lie not there.

We have in our opening article, entitled "Ancient London," glanced at the picturesque appearance of this neighbourhood in former years, and now turn to the present to find that these old world splendours have given place to gin-shops, plate-glass palaces, into which squalor and misery rush, and drown the remembrance of their wretchedness in drowsy and poisonous potations of gin; -splendour and squalor, the very contrast of which makes thinking men pause, but are disregarded by those who contribute to the one and recklessly endure the other.

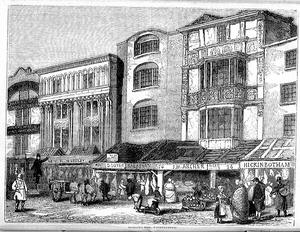

Our engraving

represents the well-known row of butchers’ shops; for the Whitechapel butcher still belongs

to the old school, taking a delight in his blue livery, and wearing his steel with as much satisfaction

as a young ensign does his sword.lie, neither spurns his worsted leggings nor duck apron; but,

with bare muscular arms, and a knife keen enough to sever the ham-string of an old black bull,

takes his stand proudly at the front of his shop, and looks "lovingly" on the well-fed joints

that dangle above his head. The gutters before his door literally run with blood: pass by whenever

you may, there is the crimson current constantly flowing; and the smell the passenger inhales

is not such as may be supposed to have floated over "Araby the blest." A "Whitechapel bird"

and a "Whitechapel butcher" were once synonymous phrases, used to denote a character the very

reverse of a gentleman; but in the manners of the latter we believe there is a very great improvement,

and that more than one "knight of the cleaver," who here in the daytime manufactures sheep into

mutton-chops, keeps his country-house.

Our engraving

represents the well-known row of butchers’ shops; for the Whitechapel butcher still belongs

to the old school, taking a delight in his blue livery, and wearing his steel with as much satisfaction

as a young ensign does his sword.lie, neither spurns his worsted leggings nor duck apron; but,

with bare muscular arms, and a knife keen enough to sever the ham-string of an old black bull,

takes his stand proudly at the front of his shop, and looks "lovingly" on the well-fed joints

that dangle above his head. The gutters before his door literally run with blood: pass by whenever

you may, there is the crimson current constantly flowing; and the smell the passenger inhales

is not such as may be supposed to have floated over "Araby the blest." A "Whitechapel bird"

and a "Whitechapel butcher" were once synonymous phrases, used to denote a character the very

reverse of a gentleman; but in the manners of the latter we believe there is a very great improvement,

and that more than one "knight of the cleaver," who here in the daytime manufactures sheep into

mutton-chops, keeps his country-house.

The specimens of viands offered for sale in these streets augur well for the strength of the stomachs of the Whitechapel populace; no gentleman of squeamish appetite would like to run the risk of trying one of those out-of-door dinners, which ever stand ready-dressed. The sheep’s trotters look as if they had scarcely had time enough to kick off the dirt before they were potted; and as for the ham, it appears bleached instead of salted; and to look at the sandwiches, you would think they were veal, or anything except what they are called. As for the fried fish, it resembles coarse red sand-paper; and you would sooner think of purchasing a penny-worth to polish the handle of a cricket-bat or racket than of trying its qualities in any other way. The black puddings resemble great fossil ammonites, cut up lengthwise; for while you gaze on them you cannot help picturing these relics of the early world, and fancying that they must have been found in some sable soil abounding in broken fragments of gypsum, which would account for the fat-like substance inside. What the "faggots" are made of, which form such a popular dish in this neighbourhood, we have yet to learn. We have heard rumours of chopped lights, liver, suet, and onions being used in the manufacturing of these dusky dainties; but he must be a daring man who would convince himself by tasting: for our part, we feel confident that there is a great mystery to be unravelled before the innumerable strata which form these smoking hillocks will ever be made known. The pork-pies which you see in these windows contain no such effeminate morsels as lean meat, but have the appearance of good substantial bladders of lard shoved into a strong crust, from which there was no chance of escape, then sent to the oven and "done brown." The ham-and-beef houses display the same love of fatness, as if neither pig nor bullock could be overfed that comes to be consumed by the "greasy citizens" of the east end of London.

As for fish! the very oysters gape at you with open mouths, as if they knew how useless it would be to keep closed in such a ravenous-looking neighbourhood. They seem to cast imploring glances at the passers-by, as if begging to be taken out of the hot sun, and devoured as quickly as possible. You see great suspicious-looking whelks, sweltering in little saucers of vinegar; and you cannot help wondering what would be the result if you attempted to eat one; and while you are thus doubting, without "doating," some great broad-shouldered fellow comes up, throws down his penny, and, making but one mouthful of the lot, lifts the saucer to his lips, and drains the last drop of vinegar, then goes, for a finisher, into the nearest gin-shop. Pickled eels, cut up into Whitechapel mouthfuls, are fished up from the bottom of great brown jars, and devoured with avidity. You can never pass along without seeing brewers’ drays unloading somewhere in the streets; and you cannot help thinking what hundreds a year Barclay and Perkins might save, in the wear and tear of men and horses, if they laid down pipes all the way from their brewery in the Borough to Whitechapel.

What little taste they display (if we may make use of so classical a phrase in contradistinction to their "palatal" or gastronomic propensities), is shewn in their love of pigeon-keeping; and many of the "fanciers" in this district can boast of possessing both a choice and an extensive stock of these beautiful birds. From this taste arise good results, inasmuch as it leads them into the suburbs, especially on Sundays, when they either carry the pigeons with them in bags or thrust them into their coat-pockets, and so wander for three or four miles out, when they turn the birds loose, both parties thus enjoying the luxury of a little fresh air. They are excellent hands at decoying pigeons, for all the "strays" that alight in the neighbourhood are pretty sure to become "Whitechapel birds." What means they use for entrapping these feathered favourites we have not been able to ascertain, though one knowing fellow told us, with a deep-meaning wink, that "it was the fineness of the climate, and a little ‘hankypanky’ business." We paid a pot of beer for the information, without asking for any clearer definition of the latter phrase.

Having thus become enlightened in the art of pigeon-stealing, we turned up Houndsditch, and visited the real Rag Fair. The price of admission’ is "von halfpenny," a toll from which neither Jew nor Gentile is exempt. This market or fair for old rubbish of every description is well worth seeing; and to whatever use the trash could be turned that met our eye in every direction, did at first, as old Pepys says, "puzzle us mightily."

Rag Fair is a market consisting of long rows of standing or sitting places, having neither back nor front, but covered in by narrow penthouse roofs, supported on beams, under which the sellers or exchangers take their places: the wind and rain blow and beat through these open sheds, both drenching and sweetening the fusty rags . that are exposed for sale. Those who wish to purchase pass up and down the "ragged" alleys. We were detained at the narrow entrance of the first row for several moments by two ancient and bearded children of Israel, who were endeavouring to bargain. The seller had the portions of two pairs of old shoes in his hand; one pair "soleless," the other nearly "upperless."

"How much for these, Mo’ ?" inquired the purchaser.

"Twopence," answered the other; "they be dirt-cheap."

Bah ! - won’t do, Mo’," was the reply, after having examined them; "could not cut off enough to stop up a mouse-hole. Say von penny !"

"Vell, den, three-halfpence !"

We passed on, and did not witness the close of the bargain, our ears being now assailed with such cries of " Who vants three vaistcoats for old coat ?" " Who vants old hats for old shoes !" "Two shirts for von pair of strong preeches ! and so on. There we saw the hook-nosed, large-eyed collector of "old do’" whom we had that very morning stopped to look at while he carried off a whole suit in exchange for two geraniums which looked as if they could not live a week. The very things he was then running down, as he pointed out every thin spot and speck of grease to the little Cinderella he was bargaining with in the Borough, he was now extolling, and vowing that they had but been worn "wery leetle, wery leetle indeed." With keen eye the intended purchaser traversed every inch, examined carefully the knees of the trowsers, the arm-pits, elbows, and sleeves, of the coat; then discovering something at last, as he shined it before the light, he pointed to the spot, and looked at the other in silence. "Vell, vot of dat ? - Look at the pryshe !" was the reply of the geranium exchanger.

There is an old and mouldy smell about the place, telling that dank and fetid corners have been rummaged out to contribute to the stock of filth there accumulated. And yet, through the dirty mass the eye may here and there detect the trappings of pride. Court-dresses, from which the former owners would now run, exclaiming with Hamlet -

"And smelt so? Pah

Small satin slippers which had once been white, but now wore a little of the hue of every foul thing they had come in contact with. The worn-out wedding dress, now a heap of rags, bundled up beside the thread-bare blackness of the poor widow’s cast-off weeds. One might almost fancy that Pride had come here to crawl out of its shabby habiliments, and gone and laid down in some one of the dark alleys in the neighbourhood to die, having "shuffled off" the last vestiges of respectability.

"To what vile uses do we come at last "

Rags that may have touched a young and beautiful duchess, not now fit for dusters. A remnant of the dress-coat of some young lord, thrown down with disdain by the hunger-bitten jobbing-tailor, because he cannot get a patch out of it large enough to seat the "continuations" of the Whitechapel hawker.