II. Whitechapel

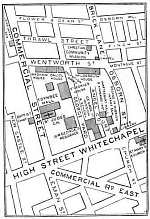

THE Aldgate entrance to the great continent which we call East London is a welcome surprise

to the stranger. Passing the boundary of the old city wall, we are at once in the heart of the

most spacious, most picturesque, and most impressive of the great streets of the metropolis.

'Of all the roads which lead into London and out of it,' says our chief contemporary historiographer

of the 'East End,' 'this of Whitechapel is the broadest and noblest by nature.' On Sunday the

closing of the shops adds to the dignity of the thoroughfare. Moreover, there is an air of historic

London all around us. Gabled houses of the time of De Foe, of Thomas Cromwell, of Strype, and

other residents in old Whitechapel; and old inns, with the relics of galleried yards of the

stage-coach period of history, are suggestive of bygone times, and of the memorable events of

which this great Essex road has been the scene.

THE Aldgate entrance to the great continent which we call East London is a welcome surprise

to the stranger. Passing the boundary of the old city wall, we are at once in the heart of the

most spacious, most picturesque, and most impressive of the great streets of the metropolis.

'Of all the roads which lead into London and out of it,' says our chief contemporary historiographer

of the 'East End,' 'this of Whitechapel is the broadest and noblest by nature.' On Sunday the

closing of the shops adds to the dignity of the thoroughfare. Moreover, there is an air of historic

London all around us. Gabled houses of the time of De Foe, of Thomas Cromwell, of Strype, and

other residents in old Whitechapel; and old inns, with the relics of galleried yards of the

stage-coach period of history, are suggestive of bygone times, and of the memorable events of

which this great Essex road has been the scene.

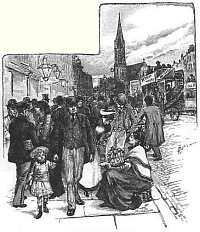

On a fine summer Sunday morning let us walk down this noble and spacious Whitechapel boulevard,

the chief and indeed almost the only open-air resort in the district for some eighty thousand

people entirely devoid of park and recreation ground.

On a fine summer Sunday morning let us walk down this noble and spacious Whitechapel boulevard,

the chief and indeed almost the only open-air resort in the district for some eighty thousand

people entirely devoid of park and recreation ground.

The stranger to the scene is at first baffled and bewildered. The roadway is filled with large tramcars, and the footways are crowded with groups of busy loungers. But we soon begin to make the great and startling discovery which awaits every new comer into Whitechapel. Here, in spite of the English-looking surroundings, he is practically in a foreign land, so far as language and race are concerned. The people are neither French nor English, Germans nor Americans, but Jews. In this Whitechapel Ghetto the English visitor almost feels himself one of a subject race in the presence of dominant and overwhelming invaders. Yet the crowds are peaceful and entirely non-aggressive in demeanour. There is no sign of lawlessness, or of molestation of the minority. Indeed, in this respect Whitechapel on Sunday, as on other days, compares most favourably with many parts of Gentile London.

The wide street continues to be crowded, although the church-bells have ceased. St. Mary's, the fine parish church, has gathered its congregation of some six or seven hundred. The Board schools are filling with Jewish children attending the Hebrew religion-classes.

At St. Jude's, in the heart of the Ghetto, the choir sometimes outnumber the congregation; and

at Toynbee Hall, close by, where Sunday morning science classes are open for students, some

scores of young men are entering with their text-books. But turning again to the great High

Street and its hurrying thousands, you would say that, in the main, Whitechapel spends its Sundays

out of doors.

At St. Jude's, in the heart of the Ghetto, the choir sometimes outnumber the congregation; and

at Toynbee Hall, close by, where Sunday morning science classes are open for students, some

scores of young men are entering with their text-books. But turning again to the great High

Street and its hurrying thousands, you would say that, in the main, Whitechapel spends its Sundays

out of doors.

Reserving for a time any detailed notice of the Christian agencies at work in Whitechapel, it will be well to give precedence to the Jewish population and the remarkable character which the Sunday is acquiring for what are known as 'communal' purposes in Jewish quarters. The synagogues, the chevras, and the Jewish Sunday schools are the three great institutions which lie in the foreground of the view. Strange as it may sound to Christian ears, Sunday, although not a day of obligation in Judaism, is, at least in the East of London, a day of considerable religious activity. In some respects, as will be seen again and again in these investigations, the Sunday religious gatherings of the Jews would appear to be of as great importance to the rising generation as the synagogue service of the preceding Sabbath.

Whitechapel abounds with synagogues great and small, with chevras, and with Sunday schools for Jewish children. The synagogues (the fact may be new to many of our readers) are by no means wholly disused for religious purposes on the Sunday. Every synagogue in East London is in fact open every Sunday, as on other days, for morning and evening service, the usual hours in summer being 7 A.M. and 7 P.M., and in winter 3.30 or 4 P.M. 'Sunday afternoon and evening,' writes a well known London rabbi, 'are of enormous service in the communal life of the Jews, the word 'communal' covering all movements having the intellectual, moral, and spiritual welfare of the community as their aim. Moreover, all meetings for religious, educational, and charitable purposes are preferably held on Sundays.'

The

synagogues may not figure largely in the street scenery of Whitechapel, or attract the attention

of the wayfarer by the sound of the church-going bell, as do the beautiful peals from the towers

and steeples of the Christian temples around. The visitor may, in fact, pass without knowing

it the Aldgate side-street where stands the 'Hebrew Cathedral' of London, the Great Synagogue,

where the office of senior warden has been filled by the Rothschild family for three generations,

and where the founder of the family is buried. A little to the north, in Bevis Marks, is the

Spanish and Portuguese synagogue. Between Crosby Place and St. Helen's Square is the New Synagogue.

The

synagogues may not figure largely in the street scenery of Whitechapel, or attract the attention

of the wayfarer by the sound of the church-going bell, as do the beautiful peals from the towers

and steeples of the Christian temples around. The visitor may, in fact, pass without knowing

it the Aldgate side-street where stands the 'Hebrew Cathedral' of London, the Great Synagogue,

where the office of senior warden has been filled by the Rothschild family for three generations,

and where the founder of the family is buried. A little to the north, in Bevis Marks, is the

Spanish and Portuguese synagogue. Between Crosby Place and St. Helen's Square is the New Synagogue.

It is not a little significant of the great influx of foreign Jews, and the multiplication of those already domiciled in Whitechapel, that within the last four or five years synagogues have been built and opened within a short distance of each other in the New Road, Vine Court, Greenfield Street, and Great Alie Street. Among the lesser synagogues are those in Scarborough Street and Mansell Street, Commercial Road, and Plummer's Row.

A still more notable sign of a rapidly increasing population and the problems which it brings in its train is the project for a new and very large synagogue in the Commercial Road, for the purpose of relieving the more congested districts of Whitechapel. It is to be called the New Hambro' Synagogue, the old site having been abandoned in favour of the less populous area farther east. The rebuilt Hambro' Synagogue is to seat 1000 male worshippers and 400 female worshippers, twice the number at any existing constituent synagogue, at the cost of some £30,000.

Religious services for children are not seldom held in the East End synagogues; but it is not here that we shall see how largely Sunday is devoted by the Jews to the education and nurture of their children, under the ardent supervision of the leaders of the community.

The Jewish Sunday schools are a great and impressive feature of the Whitechapel and East London

Sunday. The religious education of the children, as arranged by the great leaders of London

Judaism, is of the first importance, and extraordinary efforts and sacrifices are made to promote

it. The distinctively Jewish buildings of so poor a district as Whitechapel are quite unequal

to the needs of the closely-packed population, and the immense overflow of children has had

to be provided for from other sources. Accordingly the capacious new school-buildings of the

London School Board have during the last few years been readily offered and eagerly accepted

for the Sunday use of Jewish children. The result is that almost all the Board schools in Whitechapel,

Spitalfields, Mile End, and Stepney are appropriated to Jewish children on the Sunday. At the

present time there is no Board school in any district of East London, where Jews reside in considerable

numbers, which is not used on Sunday for this purpose. Any properly accredited application -

and these are increasing every year - suffices to obtain at once the necessary permission.

The Jewish Sunday schools are a great and impressive feature of the Whitechapel and East London

Sunday. The religious education of the children, as arranged by the great leaders of London

Judaism, is of the first importance, and extraordinary efforts and sacrifices are made to promote

it. The distinctively Jewish buildings of so poor a district as Whitechapel are quite unequal

to the needs of the closely-packed population, and the immense overflow of children has had

to be provided for from other sources. Accordingly the capacious new school-buildings of the

London School Board have during the last few years been readily offered and eagerly accepted

for the Sunday use of Jewish children. The result is that almost all the Board schools in Whitechapel,

Spitalfields, Mile End, and Stepney are appropriated to Jewish children on the Sunday. At the

present time there is no Board school in any district of East London, where Jews reside in considerable

numbers, which is not used on Sunday for this purpose. Any properly accredited application -

and these are increasing every year - suffices to obtain at once the necessary permission.

A visit from a stranger never fails to excite his astonishment at the number of children in attendance. At Whitechapel, the large Board schools in Settle Street, Old Castle Street, and Berner Street, Commercial Road, stand, perhaps, at the head of the list as regards children attending for instruction in the Scriptures and knowledge of Hebrew. At Old Castle Street school the number of Jewish children attending religious classes on the Sunday is often one thousand. Many other illustrations could be given, showing the concern for the education of the young which distinguishes the Jewish community as a whole, under the inspiration and organisation of the Central or Federated Synagogues, and in accordance with the whole bent of modern Anglo-Judaism.

Such, then, is the brighter and better side of the Jewish Sunday in Whitechapel, and indeed, as we shall see hereafter, in the other Jewish quarters of East London - in Spitalfields, Mile End, and Stepney. But if our Sunday visit should take us away from the great main thoroughfare, which wears its holiday aspect on Sunday, and we should turn into the side-streets, into the actual Ghetto, a far different picture presents itself. We shall be appalled at the sight, which can only be paralleled by the Jewish quarter of some Polish or Galician town. We are among the poorest and densest population of the British Isles, packed together in a state of inhuman, solid, and sodden poverty. The population of Whitechapel, which averages eight hundred to the acre, here rises to three thousand. The scenes and the problems which result from the Continental Jews' lower standard of life and subsistence have been sufficiently described in Mr. Charles Booth's recent work on Life and Labour in East London. The practical impossibility of changing the habits of the adult population is keenly felt by the leaders of London Judaism, and hence the extraordinary efforts made for educating and Anglicising the children, which are so great a feature in East London both on Sundays and throughout the week.

The great lesson of Sunday in Whitechapel, as far as the Jews are concerned, has to be told. In this single parish are congregated some sixteen thousand poor Jews. Twenty thousand more are easily included within the half-mile radius. Yet, strange as it may seem, this great and largely squalid colony is a peaceful and law-abiding population. On the larger scale it may even be said to be a moral population. Drunkenness is almost unknown; temperance societies are unheard of, for the Jew is never intoxicated. The public-houses will be full on Saturday and Sunday night, but not a Jewish face will be seen there. Personal violence towards women is almost unknown. Licentiousness among women is equally rare. Family ties are sacred. Considering that Whitechapel is overwhelmingly a colony of aliens, the consequences, socially and politically, might have been serious; a disaffected people might have becn a standing menace to London. Whitechapel might have become a Belleville. Happily, it is not the home of malcontent refugees or political anarchists. Nothing, in fact, is more remarkable on Sunday than the quiet and orderliness of a great population of aliens in faith and speech, who, from their point of view, are under no obligation religiously to observe the day, and who are, it must be said, less aggressive in the streets than many of their better circumstanced co-residents.

Such are some of the Sunday aspects of the East London Jewry. The great Jewish problem will confront us again and again, in these inquiries, and it may be that the religious and educational activities of Judaism which we have so briefly noticed will probably assume increasing importance as we trace their widening area in the great parishes contiguous to Whitechapel.

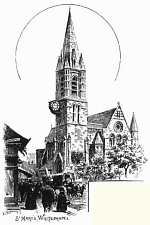

Leaving the Jews' quarter, we turn to an entirely different scene. On the opposite

side of the High Street stands a gracious beacon, the historic church of St. Mary's, Whitechapel,

with its noble spire, its open-air pulpit, and its beautiful church-garden. Even as a street

scene it is a beautiful sight; it stands for a sweeter air, a higher and more humane civilisation

than that which we have left behind us. St. Mary's, moreover, is rich in hallowed associations

and cherished names. It has for generations been the centre and fortress of East End Evangelical

pastors and preachers. Its rectors during this time have been men of note, conspicuous as preachers,

parish workers, and organisers. The names of Weldon Champneys, Cohen, Kitto, and Robinson still

stir the memory of Whitechapel citizens. The work which these able and devoted men were able

to achieve, and the inspiring examples they have bequeathed to their successors, are gratefully

portrayed in some of the most beautiful of the sculptures and stained-glass memorials which

adorn the parish church.

Leaving the Jews' quarter, we turn to an entirely different scene. On the opposite

side of the High Street stands a gracious beacon, the historic church of St. Mary's, Whitechapel,

with its noble spire, its open-air pulpit, and its beautiful church-garden. Even as a street

scene it is a beautiful sight; it stands for a sweeter air, a higher and more humane civilisation

than that which we have left behind us. St. Mary's, moreover, is rich in hallowed associations

and cherished names. It has for generations been the centre and fortress of East End Evangelical

pastors and preachers. Its rectors during this time have been men of note, conspicuous as preachers,

parish workers, and organisers. The names of Weldon Champneys, Cohen, Kitto, and Robinson still

stir the memory of Whitechapel citizens. The work which these able and devoted men were able

to achieve, and the inspiring examples they have bequeathed to their successors, are gratefully

portrayed in some of the most beautiful of the sculptures and stained-glass memorials which

adorn the parish church.

The church of St. Mary Matfelon - to give it the old historic name - is itself a message of beauty and graciousness in such a quarter. Its noble spire rises two hundred feet in height, far above the houses of the populous and struggling district around, a striking and commanding feature visible far and wide. The beautifully-toned bells are filling the air with their inviting peal. Through the crowded streets of loungers, well-to-do church-goers of the middle classes are wending their way to morning service. We enter with them, and find ourselves in a large, spacious, impressive, and richly-decorated building. The church, it should be said, is the grateful and lavish gift of a former parishioner: the lofty roof, richly-coloured walls, and the sculptures and stained-glass windows betoken alike the costliness of the offering and the giver's conception of a great church for East London. As St. Mary's, Whitechapel, is one of the foremost in popularity and equipment for parish work, and one of the best attended of the great East End churches, everything that may account for its reputation will well deserve attention.

The church seats thirteen hundred people. The services are fully choral; the Psalms are chanted both morning and evening, the congregation being led by the surpliced choir. The musical service, though keeping pace with the increasing capacities of present-day congregations, is always well within congregational lines. The growing delight in singing as an act of common worship which now characterises all Christian denominations, and which is a great feature of all East London places of worship is indeed amply provided for at St. Mary's, and that, too, in a way which shows how Evangelicalism is able without compromise to take full share of the latitude which is now so commonly assigned to congregational utterance in church.

Sunday evening at St. Mary's is a still larger and more notable demonstration of church-going, and the scene is one of the most encouraging sights which East London can show. The church is filled with at least a thousand persons of the working and poorer classes of Whitechapel. The beautiful and impressive service is an experience not to be forgotten. The sermon, too, is redolent of the place and the people. In the evening the vicar applies himself to the actual circumstances and difficulties of the congregation he knows so well. Here it may be mentioned that the population of the parish is twenty thousand, and that every family of this large number, Jew and Gentile alike, is regularly visited by the rector and his assistant clergy. Mr. Sanders can accordingly put his hand at once on the ills amidst which his people live.

Mr. Sanders' picture of the underpaid industries of Whitechapel and the results in bodies and souls of the unfortunate workers contributes important data for a view of the problem from the Christian standpoint, and seldom have the responsililities of society in this matter been stated with greater power and wiser sympathy.

'Oh, if our brother's love cry out at us,

How shalt we meet Thee who hast loved us all,

Thee whom we never loved, not loving him!

The unloving cannot chant with seraphim,

Bear harp of gold, or palm victorious,

Or face the Vision Beatifical.'

Sunday afternoon is also an occasion for meetings in church for closer dealings with the industrial classes. The Pleasant Sunday Afternoon movement, in its higher aspects, has been commenced with much success. A gospel address from one of the clergy, the services of an excellent orchestra, reinforced by the fine organ of the church, with popular hymns and sacred solos, attract a class who seldom otherwise see the interior of a beautiful church, or hear sacred music in which they can join, or get into close personal touch with the clergy. The imprimatur which the rector of such a parish has freely given to this new development of the Sunday afternoon service is naturally felt in East London to be a great encouragement. Certainly in no part of London could crowded streets give a better mandate for these social gatherings as conducted at St. Mary's.

The Sunday schools of the parish are in the front rank of the church's work. They are situate in five different quarters of Whitechapel, Jewish and Gentile alike, and are attended by more than one thousand children.

The large number of Jews and foreigners in Whitechapel is naturally felt as a claim upon the parish church. Special services for Jews are held on the principal Jewish festivals. The prayers and lessons are read in Hebrew and German, and sermons are preached in English and Yiddish (Judaeo-German). Between four and five hundred persons are present on these occasions. [1]

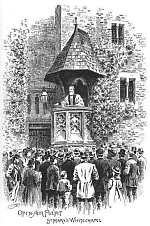

The picturesque and admirably placed open-air pulpit is a valuable means of reaching the many

passengers by this great East London highway. The large open space of the parish churchyard,

where it is placed, is in free communication with the public footway, so that the wayfarer is

easily attracted within earshot. Addresses are given every Sunday evening in the summer months

at 8.30. On Saturdays at 5 P.M.there is an address to Jews. Most

of the addresses are given by laymen. The pulpit was erected in memory of the late Dean Champneys,

one of the most famous of Whitechapel rectors. [2]

The picturesque and admirably placed open-air pulpit is a valuable means of reaching the many

passengers by this great East London highway. The large open space of the parish churchyard,

where it is placed, is in free communication with the public footway, so that the wayfarer is

easily attracted within earshot. Addresses are given every Sunday evening in the summer months

at 8.30. On Saturdays at 5 P.M.there is an address to Jews. Most

of the addresses are given by laymen. The pulpit was erected in memory of the late Dean Champneys,

one of the most famous of Whitechapel rectors. [2]

The Universities Settlement, known as Toynbee Hall, may naturally be expected to figure in a description of a Whitechapel Sunday. In what form, it might be asked, does it contribute to the religious activity of the day? Toynbee Hall is situate in almost the centre of the Jewish quarter, and is entered from Commercial Street, the great thoroughfare which unites Spitalfields with Whitechapel High Street. By its side stands St. Jude's Church, of which one of the leaders of the Universities Settlement project, Canon Barnett, was for many years the vicar. Opposite to St. Jude's is one of the most notable chapels of a former generation, the Baptist Chapel of which the late Charles Stovell was for many years the famous minister, and to which he drew by the solemnity and force of his preaching a large and influential congregation.

The

visitor will be disappointed if he expects to find Toynbee Hall a directly religious agency

established for evangelistic purposes, and undertaking or assisting in church work on Sundays.

It should at once be said that the word 'mission' does not occur in its programme, although

the intense glow of the inner personal life of Edward Denison, the leader of the movement, is

still felt in the settlement. It was in 1867 that Denison, an Oxford student who had been profoundly

impressed with the gulf existing between the rich and the poor in London, took lodgings near

the London Hospital, and tried to share his life with the poor of the district. His example

was contagious, and by the year 1874 it had become the custom for a few Oxford graduates to

spend part of their vacation in the neighbourhood of St. Jude's, Whitechapel, and to join in

some of the work of the parish. Among them was Arnold Toynbee. The intensity which Denison and

Toynbee threw into their teaching and example made a great impression on public opinion, and

the settlement at Toynbee Hall took an organised and permanent form in the year 1884. From that

date up to the present time its scope and aims have been ethical, social, and educational, and

within the limitations thus adopted its character and achievements have become well known. Toynbee

Hall is a lay settlement, and, in the words of its programme, its object is to ' provide education

and the means of recreation and enjoyment for the people of the poorer districts of London.'

Toynbee Hall 'has become a name under which a society holds together, formed of members of all

classes, creeds, and opinions, with the aim of trying to press into East London the best gifts

of the age.' [3]

The

visitor will be disappointed if he expects to find Toynbee Hall a directly religious agency

established for evangelistic purposes, and undertaking or assisting in church work on Sundays.

It should at once be said that the word 'mission' does not occur in its programme, although

the intense glow of the inner personal life of Edward Denison, the leader of the movement, is

still felt in the settlement. It was in 1867 that Denison, an Oxford student who had been profoundly

impressed with the gulf existing between the rich and the poor in London, took lodgings near

the London Hospital, and tried to share his life with the poor of the district. His example

was contagious, and by the year 1874 it had become the custom for a few Oxford graduates to

spend part of their vacation in the neighbourhood of St. Jude's, Whitechapel, and to join in

some of the work of the parish. Among them was Arnold Toynbee. The intensity which Denison and

Toynbee threw into their teaching and example made a great impression on public opinion, and

the settlement at Toynbee Hall took an organised and permanent form in the year 1884. From that

date up to the present time its scope and aims have been ethical, social, and educational, and

within the limitations thus adopted its character and achievements have become well known. Toynbee

Hall is a lay settlement, and, in the words of its programme, its object is to ' provide education

and the means of recreation and enjoyment for the people of the poorer districts of London.'

Toynbee Hall 'has become a name under which a society holds together, formed of members of all

classes, creeds, and opinions, with the aim of trying to press into East London the best gifts

of the age.' [3]

What the Sunday visitor is looking for he will find more or less realised in another University Settlement which exists a little farther north, at Oxford House, Bethnal Green. At Oxford House, as we shall see, in addition to the object sought at Toynbee, there is a distinctive church mission working on Sundays in aid of the parish churches around, as well as providing, out of church hours, definite religious teaching and holding religious services. The delivery of a gospel message to the vicious, the sin-worn, and the heart-broken, and of rescue from sin and judgment, as prior to all other objects in life, is recognised here and at other settlements in East London. But at Toynbee Hall such agencies are not now contemplated in the plan of the institution.

Looking at the Jewish character of the district, it is not improbable that Sunday science and literature classes may be much more extensively developed. Already the Museum attached to the Whitechapel Free Library is open on Sunday afternoons, as a concession to the enormous proportions of Jewish residents, and is attended by as many as sixteen hundred persons every Sunday. Sunday classes have already been opened at Toynbee Hall in literature, physiology, botany, and other sciences. [4]

The most eventful of the changing conditions of religious life in Whitechapel as affecting the future is the decline of the old sources of voluntaryism among the population. This is seen chiefly in the serious diminution in the number of the Nonconformist chapels of various denominations. It is also making itself felt in the greater difficulty of raising funds for the parish churches. The causes are not far to seek. The great diminution in the number of large employers of labour whose aid could formerly be reckoned upon, and especially the disappearance, owing to fiscal changes, of the great sugar refiners, may be cited as one, although not the most potent, of these causes. Spacious warehouses now stand empty and roofless, or are transformed for other purposes by companies and corporations who have no personal ties in the district. The further explanation is to be found in the decrease in the English population of the district, and, above all, in the almost total disappearance of the middle class, who do so much for churches and chapels elsewhere. So far has this decline proceeded that even the endowed churches can only be held by clergymen who have private means of their own, or who can obtain help from friends in the more distant and the richer parts of London. Only by means of outside subsidies from a few wealthy and generous Christian donors is it found possible to maintain the truly noble and multifarious work which is carried on at Whitechapel parish church. At present St. Mary's is maintained in its old and vigorous continuity by appeals of the rector to a circle of friends in other and richer parts of the metropolis. Only by these means is the great annual deficiency of some thousands of pounds made good, and the very varied and onerous ministrations maintained at the needful strain.

The ever increasing Jewish population of Whitechapel, apart from the social morass of the inner Ghetto, is rapidly becoming Anglicised, and the process is being attended with scrious results to the older indigenous English residents. Indeed, the last-named are being steadily pushed out of their native quarters by the irresistible competition of the new-comers. In the light of this portentous fact, the struggling and precarious condition of Christian organisations of all kinds, which need money for their support, will be still better understood. From this rapidly multiplying Semitic population, to whom Whitechapel is an El Dorado, aided by the powerful and highly creditable efforts of the West End Jews not only to humanise but to Anglicise the Ghetto, some twenty thousand Jewish children are being daily equipped for the industrial market in East London. In two or three years, all these children will have been launched into local industrial life, with an obvious result upon the balance of races and the competitive conditions of labour. The humbler standard of living and expenditure common to the poor Jew, in a district over-populated, and the increased keenness in competition for work, tend inevitably to displace the Gentile population of Whitechapel and the adjoining parishes. The process will continue probably at an accelerated rate, greatly to the religious and economic transformation of East London. We shall meet with further illustrations of it in our future glimpses of Sunday in East London.

[1] The large and almost incredible number of important evangelical, educational, industrial, and mission agencies which are at work on week days In the parish do not come within the scope of this paper. They are detailed in the rector's annual report.

[2] During the present year Mr. Sanders has left Whitechapel for Dalston, and has been succeeded by the Rev. John Draper, from St. Paul's, Bethnal Green.

[3] Annual Report, 1893.

[4] Here and elsewhere in this series of papers, aims and agencies are reported as entering into and colouring the life of the population, and as thus indicating some of the deeper changes which are proceeding In East London, and some of the newer conditions under which Christian work has now to be carried on. In this respect some account of them is indispensable to a working knowledge of the East End Sunday.