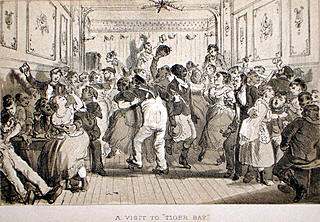

A VISIT TO "TIGER BAY."

EVERYBODY addicted to the perusal of police reports, as faithfully chronicled by the daily press, has read of Tiger Bay, and of the horrors perpetrated there - of unwary mariners betrayed to that craggy and hideous shore by means of false beacons, and mercilessly wrecked and stripped and plundered - of the sanguinary fights of white men and plug-lipped Malays and ear-ringed Africans, with the tigresses who swarm in the "Bay," giving it a name. "God bless my soul" remarks the sitting magistrate, as evidence of a savage assault in the shape of an ear snapped off a human head by human teeth, and decently wrapped in a cool cabbage-leaf is exposed to his gaze, along with a double-handful of towzled female hair, tendered on behalf of the defendant as proof of provocation. "God bless my soul! it must be a very shocking neighbourhood ?" "It is, indeed, sir," replied Mr. Inspector; "at times it is unsafe for our men to perambulate it except in gangs of three." A private individual, however, suitably attired, and of modest mien, may safely venture where a policeman dare not show his head; so, being curious to become an eyewitness of what the terrible "Bay" was like, I turned into Ratcliffe Highway at eight o'clock one Monday evening.

The earlier part of my exploration was disappointing. In the first place it was so densely foggy that the names affixed at the street corners could not be made out; and in the second, not even the policeman on his beat could inform me where Tiger Bay was. Under the circumstances, it was a ticklish inquiry to make of the police, but the member of the force to whom I addressed myself as good luck willed, was a very civil fellow, and not disinclined to conversation.

"There ain't no place of that name hereabout," said he, "you must ha' been misdirected."

"I think you must forget, policeman," I replied. "Unless the newspapers are wrong - which is hardly likely - Tiger Bay is a tolerably well-known place in this district."

"Pish the newspapers !" returned Mr. Policeman in tones of such profound contempt as naturally grated harshly on my sensibilities, "what's the newspapers? There's a precious lot appears in 'em that never appears out of 'em. Because they call places out of their hames it doesn't follow that I'm to encourage 'em."

"But can you direct me to the neighbourhood the newspapers have spoken of as Tiger Bay?" I mildly insinuated, "the locality where sailors are so shamefully used by ruffianly men and women ?"

"Oh if she-tigers make Tiger Bays, you haven't got far to travel," replied Mr Policeman, yielding slightly ; "that's one" (pointing to a black and narrow avenue on the opposite side of the way), "and two turnins higher up there's another. Brunswick Street is another. Brunswick Gardens is a goodish bit further up - little prayer-meeting place at the corner of it. P'raps that's the Tiger Bay you want. I'd rather you want it than me. They'd have the hair off a man's head if they could get a penny a pound for it. About one in the morning or a little after is the time for a fellow to take a walk through Brunswick Street."

"Why one in the morning, policeman ?"

"Because they've hooked their fish and carried it home by that time, and the public-houses being shut up, are as drunk as they are likely to be for that night. That's when the hello begins, not before; when they've choused the flats of every rap they've got about 'em, and would rather have their room than their company. Why, you might walk through David's Lane, or Palmer's Folly, or White Hart Street this time o' night with a dimond pin in your shirt, as the saying is, and not so much as get it once snatched at. The tigers, as you call 'em, are all out hunting."

I expressed my sense of the obligation Mr. Policeman had conferred on me in terms that not only touched his heart but moved the forefinger of his right hand as high as the peak of his helmet, and then ventured further to inquire as to the favourite hunting grounds of the she-tigers. He was good enough to specify several. "There's the Globe and Pigeons," said he, '"and the Gunboat, and the Malt Shovel, and the White Swan. 'However, if you want to find the last mentioned you mustn't ask after it by the name I've give it, which is the proper name; you must ask after it as 'Paddy's Goose;' that's what they call it in these parts."

I took leave of my friend, and walked up the Highway not a little perplexed as to what was to be done. I had come on purpose to view Tiger Bay - to witness what the constable graphically described as the "hello" when at its fullest blast. That, however, could not be; it was not yet nine o'clock, and the "hello" did not commence until one. Besides, I was bound to confess to my dissatisfied self that I had been a little out in my calculations as to the nature of the said "hello."

I had imagined Tiger Bay to be a region of public, and not private houses—a place where an unobtrusive individual might spend an hour or so taking mental notes, nobody troubling his head about the matter; now, however, I had learned that it was a mere stronghold of dens to which were carried for picking and plucking the game after it had been run down and tethered, and I did not see my way quite so clearly. And in this unsettled condition of mind I went along, when suddenly the enlivening strains of music greeted my ear, and, looking towards the spot from whence it proceeded, beheld the "Globe and Pigeons" inscribed on a lamp. This was one of the camps of the "hunters" Mr. Policeman had mentioned.

Without further reflection on the matter, I crossed over, and, pushing open the swinging door, found myself in view of a dingy bar (still adorned with the garlands and mistletoe of Christmas), before which an old tigress, aged about sixty, and two young ones (one quite a cub—you could see, when she opened her mouth to sweat, that her baby teeth were yet serrated and ungrown) were drinking gin. A mariner had "stood" the gin, and there leant against the counter with his face on his folded arms, his cap on the back of his head, and his favourite fore-lock dabbling in the glass of liquor that had been generously allotted him out of the half-pint he had paid for. I don't know whether he was crying, but he spoke as though he was, and with gin in his heart, gin in his head, gin in his hair, he was murmuring complaints against the eldest cub of the two on the score of her infidelity. The young tigress was for growling and showing her claws, but the gray old one wagged her head against any such premature proceeding, and poured out the cub some more gin, doubtless to assist her in bearing up against the mariner's unjust aspersions.

Passing this party, I spied a passage, and across the end of it hanging curtains of dirty chintz, through the chinks of which shone the glare of gas beyond; likewise there was to be heard the scraping of feet against the floor, and the twanging of a harp, and the shrill piping of a cornopean. No one hindering me or requiring to know where I was going, I approached the calico barrier to the realms of bliss, raised it, and entered.

If the spectacle revealed was not enchanting, it was at least highly curious. It was like being "behind the scenes" at a theatre during the pantomime season. A barn-like, long, narrow building with whitewashed walls, on which in flaming colours were a series of hideous pictures illustrative of the domestic habits and customs of the Chinese. There was a big fire-grate in the place, with a broad mantelpiece, on which reposed short pipes and splints, and a quart pot with beer in it, and with one of her naked arms resting lovingly against the pot, and a foot on the fender, stood the most magnificent female it was ever my lot to behold. Her hair was economized in its ornamentation of her fair head by a coronet of green leaves and pearls, and her maiden blushes were modestly screened from public gaze by a substantial coating of some ruddy pigment; her bodice was low, as were not her skirts, and she wore scarlet shoes with brass heels. Yet for all these fairy-like attributes she was not proud, for with his foot on the fender, and his elbow on the shelf; and a particularly short and dirty pipe in his mouth, stood a dirty-faced, unpleasant-looking person (the potman of the establishment), and she was talking quite familiarly with him.

The

dance was just finished as I entered, and the mob, composed of tigresses and mariners (sailors

of colliers as far as I could make out), mingled freely and partook of each other's beer. As

for me, I took a seat in a corner, but had scarcely settled myself when up came a second fairy,

the facsimile of the first, but shorter and somewhat thicker, and said she to me,

The

dance was just finished as I entered, and the mob, composed of tigresses and mariners (sailors

of colliers as far as I could make out), mingled freely and partook of each other's beer. As

for me, I took a seat in a corner, but had scarcely settled myself when up came a second fairy,

the facsimile of the first, but shorter and somewhat thicker, and said she to me,

"Did you say 'bacca ?"

"I did not say 'bacca, miss; what made you suppose that I had ?" I replied.

"Cause I've got it—screws and arf ounces, as well ; an' cigars; and if you wants any you may as well have it of me."

And as she spoke she revealed a tumbler with the goods she mentioned in it. I did say, "'bacca "now, seeing that she had rather I would, and I gave her twopence for "arf a ounce" of it.

Discovering this second one, I looked about me for other fairies, but no more were discoverable. These were the only two, and they were the regularly engaged "dancing girls" of the establishment. This was evident, for on the musician stamping with his foot to notify that he was ready when his customers were, and no one being in a hurry to respond, the potman before mentioned called out to one of the fairies, "D'ye hear, Loo? Keep the game alive;" on which Loo seized on a mariner and danced him to the middle of the barn.

Her sister was likewise adjured by the authority before mentioned to keep the "pot bilin'," and though she still held the glass with the screws and arf ounces in it, and somebody had presented her with a ham sandwich, which occupied her other hand, she responded to the call with alacrity, tripping it before her partner, and supping on the bread and bacon the while. As for the tigresses assembled (a poor lot, by the way, and looking very shabby contrasted with the fairies), they didn't care a fig for dancing, preferring to purr and paw their victims to good humour at their ease; but the victims had come there to dance, and dance they would, so the tigresses were compelled to rise on their able legs, and stump through a polka or two with them.

Having my misgivings whether the Globe and Pigeons hunting ground was a fair representation of its kind, I by-and-by finished my beer, and slipped out. As I passed the bar I heard one mariner whisper to another that he had "had enough of this," and was going up to the Gunboat, so, keeping in his wake, I presently found myself at the hunting ground so named.

Along a passage exactly similar to that pertaining to the Globe and Pigeons (screened by exactly similar curtains), and except that it was somewhat larger, and had a sort of raised platform at the end, I found myself in an exactly similar barn, just as dirty as to its walls, and bespattered with saliva as to its floor, just as uncomfortable in every possible respect, and as suggestive of the wonder how it could prove attractive to any class of men possessed of the least degree of sense or decency. Here the tigresses assembled in greater numbers than at the Globe and Pigeons, and were of a different class, being better dressed, and ten times bolder and more foul-mouthed. From what stock they originally sprang is a mystery. It seems that they must have been from one and the same. Take fifty of them, and, setting aside trifling variations as regards complexion and colour of hair and eyes, they would pass as children of the same parents. The same short, bull-like throats, the same high cheek-bones and deep-set eyes, the same low retreating foreheads and straight wide mouths, and capacious nostrils, the same tremendous muscular development stamps one and all.

The sailors, too, were different from those met at the Globe and Pigeons, being, as could easily be seen, men in the merchant service. I am glad that I could make out no man-o'-war's men amongst them, since truth compels me to declare that a more spoony or weak-minded crew it was never my misfortune to fall in with. There was not a spark of dash or devil-mar care hilarity amongst them. There they sat (when they were not engaged in mooning through a dance), swilling beer, and gin, and rum, and shelling out their hard-earned money like melancholy idiots as frequently as the muscular tigresses chose to demand it of them, and submitting to abuse and insolence, and not unfrequently slaps on the face, tamely as henpecked husbands. Matters in this respect must have sadly altered since Mr. Dibdin lived and wrote. Once upon a time, as we have reason to believe, there was truth in the maritime stave in which occur the lines –

"If we've peril on the seas, my boys,

We've pleasure on the shore."

Pleasure! Perilous indeed must be the ordinary occupation of the man who can find delight and relaxation in being bullied and contemptuously treated by a brawny-armed, big-knuckled, wretch, whose breath is pestilence and her language poison. Where amongst all these petticoated creatures was to be met the kind-hearted "Molly," who studied to an atom of sugar the flavour of her Thomas's grog, and was so sedulous as to the spotlessness of his unmentionables? It is scarcely saying too much that not one woman in ten getting drunk at that Wapping Gunboat would have scrupled to doctor her Thomas's grog with a dose of laudanum, while her only care as to the clean or dirty condition of the before-mentioned unmentionables would be the difference it would make in the price they would fetch at the "Dolly Shop," after she had stolen them from him.

She is an arrant thief, the modern Molly of Wapping, as it was my painful lot to witness in the same Gunboat dancing-room. There was a young man there, not a common sailor I should judge from the cut of his clothes, and, being a fool like the rest, he went on melting his money in a rum measure until he came to the last of it. But he was youthful and gallant. So when a siren, with an arm which, delivered straight from the shoulder, might have floored a prize-fighter, tweaked him imperiously by his budding beard, and demanded "another jorum," he told her that he "hadn't another shot in the locker," but she might take his jacket, and sell it if she liked. "If I like !" replied the tigress, with a laugh louder than the dance music; "why, I'd sell your — life if I had the chance." So he took off his heavy pilot jacket, and while her companions yelled at the fun, she ran off, and in less than two minutes returned without the jacket, and with what might have been a shilling's worth of rum and water. That this was all the poor young man got for his property I am certain, for presently he made the unwelcome discovery that he had run out of tobacco. "Damme, Eva! (Heavier, it should have been) I've got no baccy 1" "Then you're lucky in havin' a wesket as is as good as money," responded the gentle Eva, and instantly acting on the hint the gallant young fellow divested himself of this article of apparel, as well as the other (I was glad to perceive that he wore a coloured woollen shirt beneath), and, stepping fleetly off with it, his sweetheart promptly returned with half an ounce of tobacco as its equivalent. There was an old tigress of the Jewish persuasion who witnessed this little stroke of business, arid even she called "shame " but on being threatened with a "oner in the mouth" if she did not confine her attention to her own affairs, she prudently had no more to say about it.

I may as, well mention that the amusements provided at this establishment differed materially from that offered at the Globe and Pigeons. Besides dancing, at the Gunboat there was clog-hornpiping and comic singing. For some time I had noticed a wretched-looking little boy with a.monstrously big head, attired in a tight-fitting dress of some light-coloured material and with wooden shoes on his feet. He crept close to the fire, looking very unhappy and sleepy and surly, and I very much pitied the child (he could not have been, more than eight years old) and wished it had been in my power to send him to bed, as a poor little drudge who had been hard at it all day cleaning pots and kettles and running about with beer. But lo! he presently turned out to be one of the "talented Company." "Master Whatyercallem will oblige with a clog dance," cried the landlord (who was likewise M.C. and evidently on the best terms with the tigresses), and at once the young gentleman, whose name I couldn't catch, shuffled to the Platform end of the room and commenced wearily footing it to the soul-stirring music emitted from the piano. "Chuck it out, Bill! chuck it out," the M.C. called in a sharp reproving tone, and Bill "chucked it out?' spitefully, as though it was his malicious design to split his clogs and put his proprietor to the expense of buying him a new pair. However, he made a tremendous clatter, and appeared to give general satisfaction.

The comic singing was performed by the waiter, a poor object in shabby black, lame of a leg, and with a wen on his forehead. "Mr. Sidney Barry will be the next entertainment" was announced, and, limping to the stage and hunting out an old white hat from amongst some lumber that happened to 1ie there, Mr. Barry put it on, and with a stick in his hand proceeded to make an entertainment of himself. His song was an Irish song entitled "Paddy don't care," and its success with the audience seemed to depend entirely on the singer's ability to deliver himself of a roaring devil-may-care laugh and dealing a terrific whack to the floor boards at the close of each verse. The waiter had no voice for singing, but long practice had made his drunken laugh perfection itself; and he was tolerably strong in the arm, so that the applause was universal, and quite a brisk shower of copper money fell on the platform as the reward of his exertions.

Quitting the Gunboat, I discovered and looked in at the other hunting grounds Mr. Policeman had mentioned, but in the main they were all alike. There was the spoony sailor, and there was the tigress of the Bay. At some of the larger houses, such as Paddy's Goose, and the Angel and Crown, and the Sailors' Saloon, her coat was sleeker and glossier - she sported amber and satin and blue and ermine (very favourite with the well-to-do, middle-aged, and corpulent tigresses), but she was still the same heartless, cold-blooded animal, with a mouth brimming with blasphemy, and claws concealed beneath her dainty kid glove ready for rending and pillage. I don't see what is to be done with her, but decidedly she is a person to be put down – or at least checked in her depredations on the kind-hearted donkey in the blue-jacket, who, knowing woman in no other shape (for your tigress in brown serge or blue satin infests every port), is content to pay homage to her in this, and wag his head good humouredly while she bullies him, and call it a "spree" when she robs him, and goes to sea again and again, filling his glass to her amongst his foc'sall mates a thousand rniles at sea, and toasts her as "Faithful Poll of Wapping.".